|

|

MVAHG Geophysical Surveys

Resistivity survey at Corhampton Down

A geophysical survey is a non-invasive method of finding 'anomalies' (changes) beneath the earth's surface. This is an ideal technique

for archaeologists to learn more about the site before excavation. It is carried out by using the two complementary methods of resistivity

and magnetometry.

MVAHG volunteers have to date conducted over 40 geophysical surveys throughout the Meon Valley finding evidence of Iron

Age, Roman and Anglo-Saxon settlements.

Magnetometry survey at Old Winchester Hill

The following pages give details of:

- Surveying methods - resistivity and magnetometry

- Interpretation of the results

- Metal detecting surveys

- Historical and Pilot surveys carried out during the Saxons in the Meon Valley Project

Our past surveys from 2015 onwards can be accessed in the Members' section. These include the

professional reports written by Dr Nick Stoodley, FSA, together with a full report on the surveys conducted during 2013-15 as part of the

Saxons project.

Surveying Methods

MVAHG - Geophysical Survey

A geophysical survey is a non-invasive method of finding 'anomalies' (changes) beneath the earth's surface. This is an ideal

technique for archaeologists to learn more about the site before excavation. It is carried out by using the two complementary methods

of resistivity and magnetometry.

The location of the site is determined by a number of factors. These include researching historical records, aerial photos and the

PAS for a high concentration of artefacts found by metal detectorists. Permission to survey the site has to be obtained from the

landowner and as many are on farmland, surveys have to be carried out when there is no crop in the field.

The first step in conducting the survey is setting up the grid from an established baseline. The size of each grid is normally

30 m x 30 m, but can be 20 m by 20 m, or 10 m x 10 m. Lines with markers at 1 m intervals are then laid out across the grid and are

moved after each traverse. The grid is traversed in a methodical way using either magnetometry or resistivity.

Resistivity Survey

Resistivity involves passing an electrical current through the soil in order to read what lies below the surface. As soils

containing water conduct electricity more effectively than natural features, the data recorded will show the variance of features as

the probe is moved over the ground. This method can detect ditches, large pits, wall footings and non-magnetic features. It involves

moving a frame along at 1 m intervals across the grid, automatically recording the data. Each 30 m x 30 m grid takes approximately

45 minutes to complete. This can be completed in relays, with participants making half a dozen traverses or so and then another

person taking over. The data from each grid can be downloaded and viewed on site.

Magnetometry Survey

Magnetometry measures the deviation in the earth's magnetic field. This method can identify thermo-magnetised features

such as kilns and furnaces, as well as in-filled ditches and pits. It involves walking with a hand-held 'gradiometer' at knee height

at a steady pace at measured intervals. The data is automatically recorded. As we are detecting changes in the earth's magnetic

field, participants must be entirely metal free. This means dressing in clothing without zips, buckles, pins, jewellery or glasses

etc. Each person must be checked before they begin using the gradiometer to ensure there is no variation in the machine's readings,

otherwise the results will be compromised.

Magnetometry is a more rapid method of survey than resistivity; each 30 m x 30 m grid usually taking approximately 30 minutes.

However, it is preferable that one person completes an entire grid to ensure the uniformity of the data collected. Again, the data

collected can be downloaded on site to see the results.

As a volunteer, you will have the opportunity to take part in 'res' or 'mag', walking the grid with the resistance frame or

gradiometer and moving the lines.

Processing The recorded data is downloaded and post processed using specialised software. Each grid is

aligned with its adjacent grids to form a composite picture of the surrveyed area.

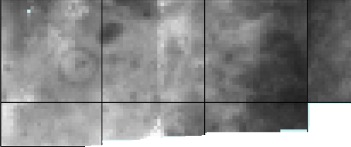

Example Resistivity Results

Example Magnetometry Results

Interpreting the Results of a Geophysical Survey

MVAHG has carried out over 40 geophysical surveys in the Meon Valley since 2014. A geophysical survey is a non-invasive method of discovering archaeology beneath the ground. The results of geophysics can be used to determine whether or not a site is suitable for excavation. The two complementary methods of Resistivity and Magnetometry are used for surveying.

We have been fortunate to have had the loan of survey equipment from Historic England since 2014; a Fluxgate gradiometer (for magnetometry) and a RM15 resistance meter (for resistivity). Furthermore, we have been expertly advised and trained by Andy Payne, HE Archaeological Geophysicist at Fort Cumberland. Dr Nick Stoodley, FSA, has led the geophysical surveys from the inception of MVAHG until stepping down in September 2022. In addition, Nick has compiled detailed professional reports for these surveys. The surveys are now led jointly by three MVAHG Trustees who each have acquired more than 8 years’ experience of carrying out geophysical surveys.

Examples of our survey results and interpretation

The data is collected by the operator traversing a grid (usually 30 m x 30 m) at measured intervals using the resistance meter (resistivity). Later the same area is traversed by the operator using a gradiometer (magnetometry). Each separate set of data is downloaded and the grids bolted together to form a composite picture of the area, using Geoplot software. The figures below are examples of data collected during geophysical surveys. At a particular site, one method of geophysics may be more responsive than the other method. This is particularly apparent in Example 2 where magnetometry provides greater definition of the area. However, both methods are complementary, so it is best to carry out both ‘res’ and ‘mag’ to obtain a complete picture of the site.

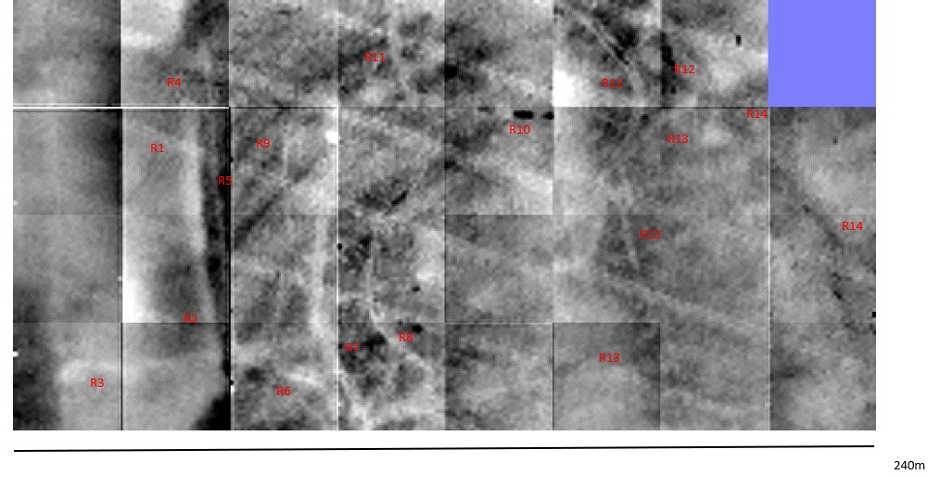

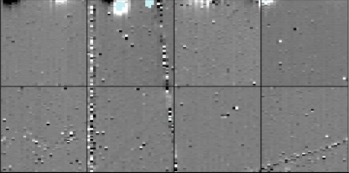

Example 1 (Field in West Meon, survey conducted in 2015)

In this example, the resistivity reveals more features, with better definition, the ground than magnetomtery. However, the magnetometry data is useful too revealing a few sub-circular features. Both methods capture the strong linear feature dominating the results.

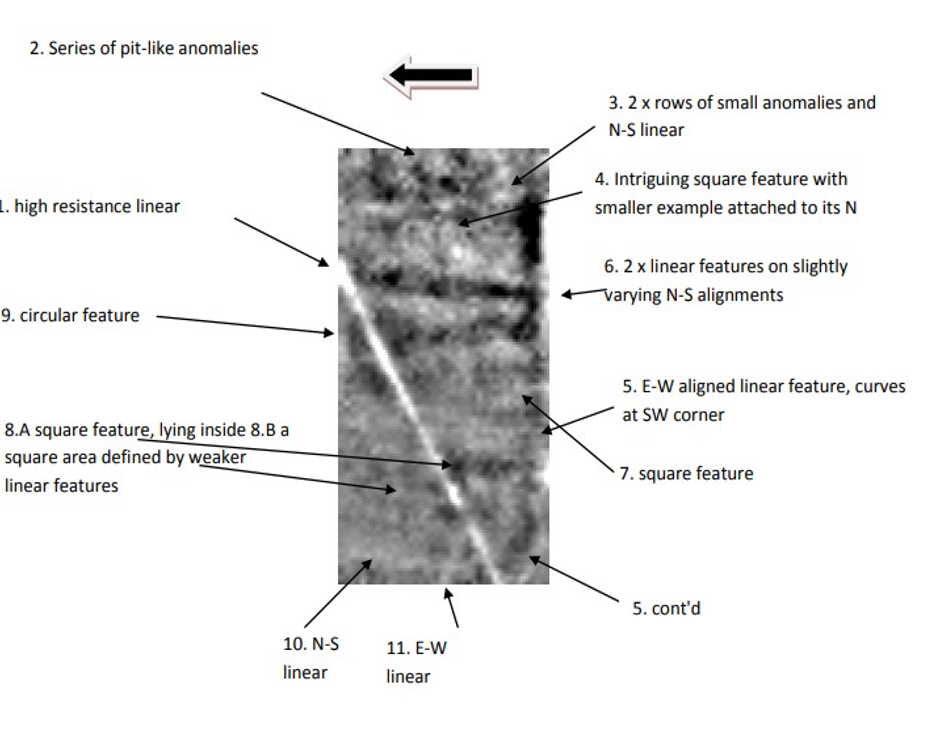

Example 1: Resistivity Interpretation

Example 1: Magnetometry Interpretation

Example 1: Resistivity(l) & Magnetometry(r) comparision

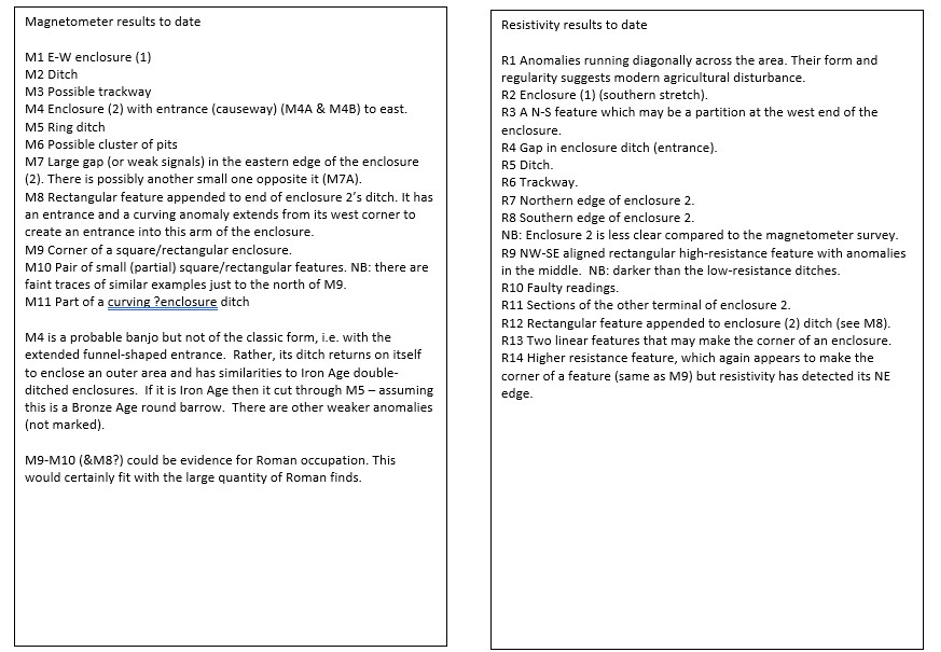

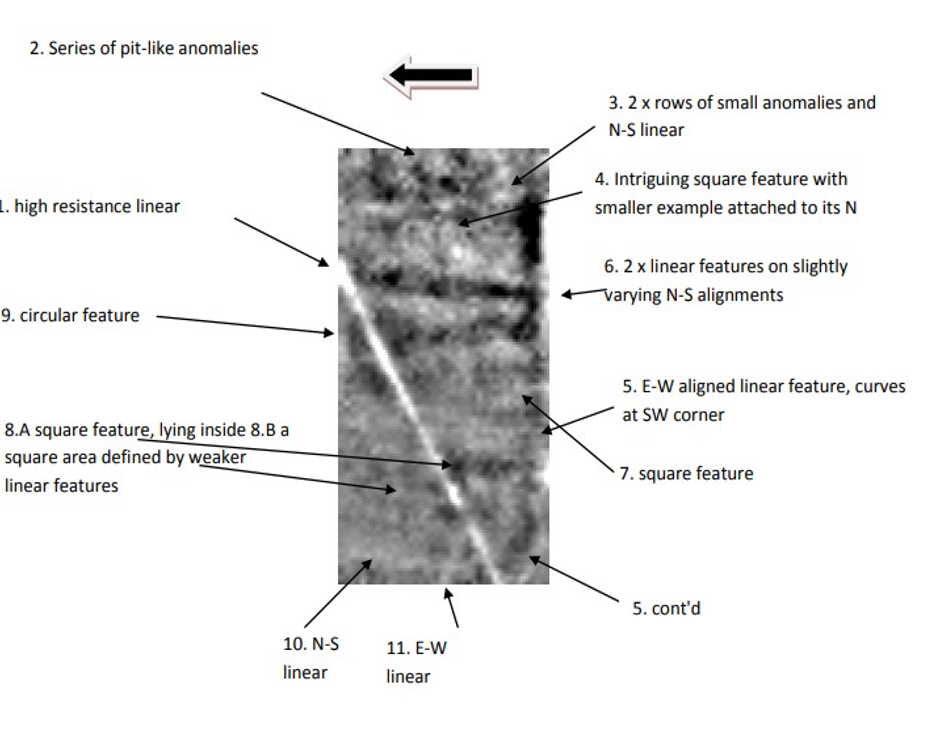

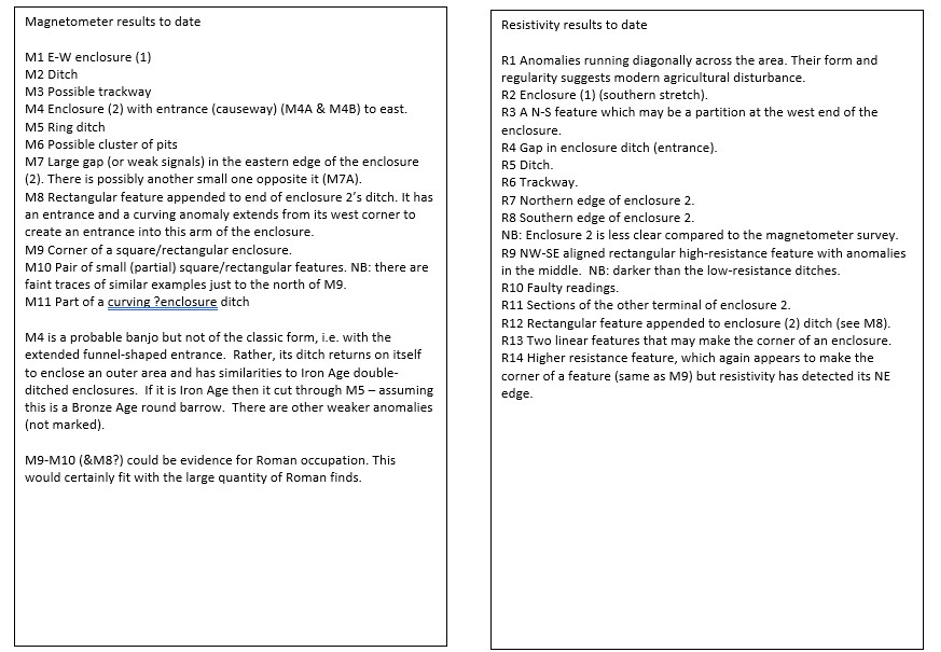

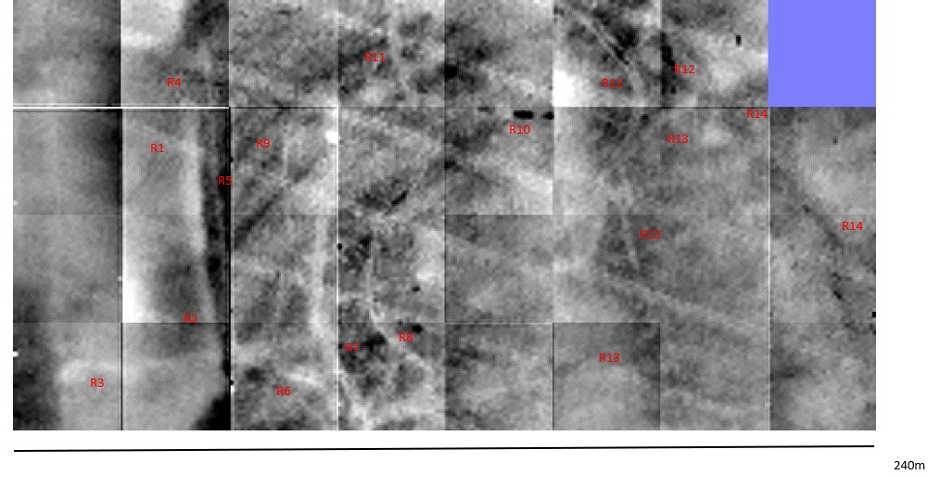

Example 2 (Field in Corhampton, composite from several surveys conducted in 2017-8)

At this site, the magnetometry data provides greater definition of anomalies lying beneath the surface; revealing a series of enclosures and pits. The results are less clear in the resistivity although similar circular and linear features are indicative in both methods. The results show various enclosures, probably of Iron Age origin, including a ‘banjo’ enclosure, which would been used as corral for cattle. A ring ditch is also featured – a probable Bronze Age barrow.

Example 2: Magnetometry Interpretation

Example 2: Key to Features

Example 2: Resistivity Interpretation

MVAHG - Metal Detecting

John & Richard detecting during a MVAHG geophysical survey

Detectorists play an important role in the selection of a site for geophysical survey. Working alongside detectorists can produce a much greater understanding of the site by comparing the results of a survey, together with further finds made by detectorists. At an excavation, detectorists can sweep a spoil heap and discover minute artefacts encased in soil, that otherwise might have been missed by the ‘digger’.

MVAHG use experienced detectorists who report finds to the PAS (Portable Antiquities Scheme) and who comply with the Code of Practice for Responsible Metal Detecting in England and Wales (2017) and the 1996 Treasure Act (recently amended). We have worked with detectorists Mike, John and Richard for a number of years and more recently with Tobin. All have made a valuable contribution to the understanding of the history of settlement in the Meon Valley by the artefacts they have unearthed.

Mike and John made special finds at one site during a MVAHG geophysical survey in 2017, unearthing two gold solidi which are now on display at Winchester City Museum.

Winchester City Museum | Hampshire Cultural Trust (hampshireculture.org.uk)

The first coin to be unearthed at the site back in 2017 was a solidus of Constans, struck at Trier in AD335-6. The other coin found close by, a solidus of Constantine II, was struck at the Mint of Siscia, AD 337-40. Both Mike and John commented that this was their best find in all their years of detecting (more than 50 years combined!).

John holding the coin of Constans (Obverse: Bust right, laureate draped and cuirassed; FL IVL CONSTANS NOB CAES)

Tribute to Mike Gaines

Mike Gaines detected with MVAHG from 2013-2018 and sadly passed away in November 2022.

‘His discoveries were valuable for the establishment of the Saxons in the Meon Valley project and its evolution into the MVAHG’ - Nick Stoodley

Mike Gaines detecting at one of our geophysical surveys in 2017

We are very sad to report that Mike Gaines passed away on 22 November 2022, following a serious fall and spell in hospital. Mike was a highly skilled and respected detectorist, who had honed his hobby for over 40 years making many important discoveries in the Meon Valley and Hampshire.

Mike had a career as an electrical artificer in the Royal Navy and was in a sister minesweeper with MVAHG Chairman Guy Liardet in Malta in 1959. However, it was in 2013 that he joined the Saxons in the Meon Valley project (later to become MVAHG), detecting during geophysical surveys and excavations. Notably it was Mike’s detecting at a site in Exton which led to MVAHG carrying out geophysical surveys here. This in turn led to the discovery of the ‘Temple Site’ and 5 years of excavating this unique site which included a Roman temple, bath-house suite and mausoleum. Without Mike’s initial detecting, kindly sanctioned by the owners, we may never have made these discoveries.

His finds are too numerous to list, but span many eras from the Bronze Age through to the 20th Century. His work for us has unearthed many important artefacts, including a rare solidus of Constantine II (337-340), mint of Siscia. On finding the coin Mike commented: “It was a real privilege to have found such a beautiful artefact and an unforgettable experience, I have found a number of gold coins over the years that I have been metal detecting but for condition and rarity this one tops them all.” This coin has been acquired by Hampshire Cultural Trust and is now on display at the Winchester City Museum.

Selected finds:

Above two of Mike’s finds from the Meon Valley:

Left: A 6th century Saxon square headed brooch length approx. 4 cm. This was exhibited at the British Museum before being returned to Winchester City Museum.

Right: A 6th century Saxon disc brooch diameter approx. 1 cm.

Mike commented on finding this: ‘When I first had the signal and dug down all I saw was a small green disc which was lying flat, and I thought at first it was a coin. But as I lifted it from the hole I noticed the tell-tale pin connections and guessed it was some kind of brooch. When I turned it over and saw the masked face still coated in gold I almost fell over in shock at what I had found. It was only about a cm in diameter but was stunningly beautiful and in wonderful condition. It now resides in Winchester City Museum.’

Above: another of Mike’s finds from the Meon Valley;

Iron Age Gold Quarter Stater coin (circa. 50 BC) Obverse (left) Reverse (right)

Mike was always willing to show his finds collection and impart his knowledge on these artefacts to others. He kindly loaned a display cabinet of locally found artefacts for the Corhampton 1000 celebrations last November.

Fellow detectorist and friend John Whittaker said:

‘Mike had been more than kind to me since I first came across him over twenty years ago while I was walking with my wife Sam through farmland. I was already ‘into’ metal detecting and went over to him to see how he was getting on. The outcome was that, unprompted, he asked if I would like to join him on the farm, checking with the owner if I could have permission to search, and we then detected happily together for many years. I’ll be forever grateful to him for being willing to share his own ‘exclusive’ sites; not everyone would have done this.’

MVAHG Treasurer John Snow expressed his thanks to Mike who kindly gave John permission to reproduce Mike’s map showing the distribution of coins he had detected at a site in Corhampton. John included this document in his dissertation.

Detectorists Mike Gaines and John Whittaker in front of their cabinets of locally found artefacts at the Corhampton 1000 celebrations in November 2021

We sincerely thank Mike for all his hard work detecting with MVAHG over the years, sharing his knowledge and making a valuable contribution to our group. It was a privilege to work alongside him.

Pilot survey at Shavards Farm, Meonstoke, 1st/2nd November 2013

The Project’s second Pilot Survey* took place in Meonstoke at Shavards Farm. Over the last 25 years this location has witnessed

several important excavations and fieldwork projects. The farm boasts an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery and middle Saxon settlement, but

is most famous for the excavation of a Roman aisled building during the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, which uncovered part of a

fallen wall. The wall was so well preserved that it was possible to reconstruct what the front of the building looked like; a section

of the wall was lifted and is now on display in the British Museum (link).

The excavation of this building also produced early Saxon settlement features, in the form of a sunken-featured building and a group

of post-holes that were cut through the top layers of the Roman building. That the Saxon evidence was directly associated with the

Roman building is significant and raises the question why the site was reused.

A community project was planned to investigate this issue, in addition to finding out more about the Roman phase. Did the building

belong to a wider site, a villa perhaps? As at Corhampton, the fieldwork was also used as an opportunity to introduce and train

local volunteers in non-intrusive archaeological techniques: magnetometry and resistivity (two forms of geophysical survey) plus

metal detecting. We were pleased to welcome back several of the volunteers from the Corhampton survey.

On the Friday, Rachel and Jen from Wessex Archaeology provided training in the use of the geophysics equipment, while on the Saturday

they were joined by Maisie and Sophie from the University of Winchester. Project members, Mike and John, led the metal detecting.

Work commenced on the Friday and although the weather forecast was rather ominous it remained mostly dry and progress was excellent.

After a brief introduction to the area and its Roman and Saxon background the volunteers divided into groups. One group set about

gridding out the area within which the geophysical surveys would take place. The importance of having accurate grids that acted as

the recording framework for the surveys was explained to the volunteers. The second group were metal detecting and full instructions

were given on their use, e.g. interpreting the different signals that metal objects produce and how to locate objects effectively by

adopting a systematic and rigorous approach.

An area covering the location of the original excavation, plus a stretch of ground to either side of it was gridded out

(60x40m divided into six 20m squares) and both magnetometry and resistivity survey was carried out. Two types of magnetometer were

used: a Geoscan FM-36 fluxgate gradiometer (Fig. 1) and a Bartington Grad601 Single Axis Magnetic Field Gradiometer System (Fig. 2).

The latter has twin probes and can collect twice as much data compared to the older Geoscan. Magnetometry is based on the measurement

of differences in the earth’s magnetic field. Metal artefacts and materials that have had their properties altered through heat,

such as brick, will cause disturbances in the earth’s magnetic field and can be detected. In this way archaeological features, such

as brick/tile structures, hearths and spreads of disturbed building material, as well as pits and ditches that are filled with

ceramic building material, for example, can be detected. The resistivity survey used 1m intervals and transects and a RM15

resistivity meter was used. For a brief explanation of this technique see the Corhampton survey.

Fig 1. Using Geoscan FM-36 fluxgate gradiometer

Fig 2. Magnetometry with Bartington Grad601 System

Very good progress was made and the whole area had been surveyed by mid afternoon. The preliminary results were very encouraging:

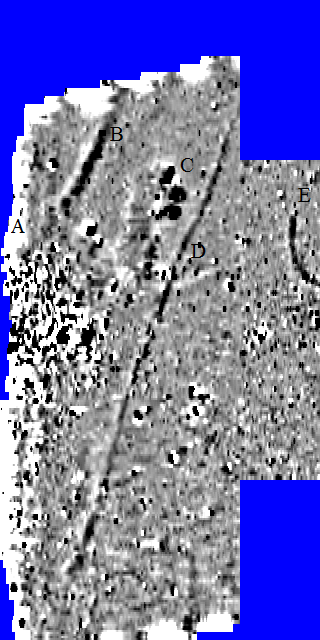

a large linear feature was clearly visible running in a NE-SW alignment throughout the area (Fig. 3, D). It was decided to survey

some additional grids with a view to identifying further evidence for this feature and to gauge whether it continued on the same

alignment or turned in a particular direction, as such information could help interpret its function. The results at the end of the

day showed that it continued straight through the area and followed the same alignment as the Roman building.

Metal detecting took place outside of this area to ensure that there wasn’t interference between the various types of equipment.

It was hoped that metal detecting would result in the recovery of artefacts that could contribute to our knowledge of the date and

cultural associations of the Saxon settlement. Unfortunately, very few artefacts were found, probably because the area has already

been searched on a number of occasions.

Saturday was cool and windy, but despite what was threatened there was only one, albeit very heavy, rain shower. In the morning

metal detecting relocated to a field known locally as the ‘Grinch’: an area to the north of the site which locals believe contains

the site of an old ford across the Meon. It is understood that this field had not previously been searched by metal detectors so the

potential for recovering artefacts was high. Once again very little material was found; yet this negative evidence is important. It

is known that the lower part of the field occasionally floods and given that the water table would have been higher in Roman and

Saxon times it suggests that settlement would probably have avoided the area. On the basis of this we can start to reconstruct the

landuse around the Roman and Saxon sites. In the afternoon the detectorists relocated to a field to the south of the building which

has previously produced a range of Roman finds. As can be expected from an area that has already been detected, the finds weren’t

spectacular but a small collection of Roman coins were recovered.

Encouraged by the results from the geophysics, the decision was taken to move eastwards up the field and survey an additional row

of 3x20m grids. By the end of Saturday the area had been completed and we waited patiently as the data was processed. The resulting

plot clearly showed the area of the excavation as a rather messy looking blob characterized by a mix of high and low readings

(Fig. 3, A). It is known that the end of the excavation was marked by a party and that empty beer cans were thrown in the excavation

trench! It is these metal cans that probably gave the high readings. More archaeologically significant are the features shown on

Fig 3.

B) NE-SW linear feature that appears to end close to the Roman building. Probable field boundary of Roman date (based on

relationship to Roman building)

C) Three pit-like features. Possible large pits or sunken-featured buildings found close to where Saxon settlement features were excavated.

D) NE-SW linear features running across area. Field boundary or boundary to the Roman site (based on relationship to Roman

building)

E) Part of a circular feature with an ‘entrance’ to the NW. Possible circular enclosure.

Fig 3. Preliminary Magnetometry Results (annotated)

The geophysical surveys have been successful in identifying the wider environment of the Roman and Saxon site. The key findings

are the boundaries (B & D) which go some way to revealing how the land, which was presumably farmed during Roman times, was organised.

The three areas that returned very high readings (C) could be Saxon sunken-featured buildings filled with Roman ceramic material.

That they appear to respect the field boundaries suggest that the settlement was taking place within the pre-existing land unit –

the earlier arrangements were determining where Saxon settlement took place and this may indicate that the Saxons were farming some

of the old Roman estate. Of course all this is very tentative: there is no evidence as yet to prove that the features (C) are Saxon;

definitive evidence can only be provided through excavation.

Overall, the results from Shavards Farm are very interesting, but as is often the case in archaeology they raise more questions

than answers. The area clearly has potential as revealed by the fact that the full extent of the features have not been mapped. As

the area lends itself to geophysical survey so well a follow up survey may well be scheduled. The experts enjoyed the two days they

spent at Shavards Farm and we would like to thank all the volunteers for their hard work and enthusiasm

*The Pilot Surveys are an opportunity for the experts to refine their approaches, not only in how we implement and carry out

surveys but also how we deliver training to volunteers.

Nick Stoodley

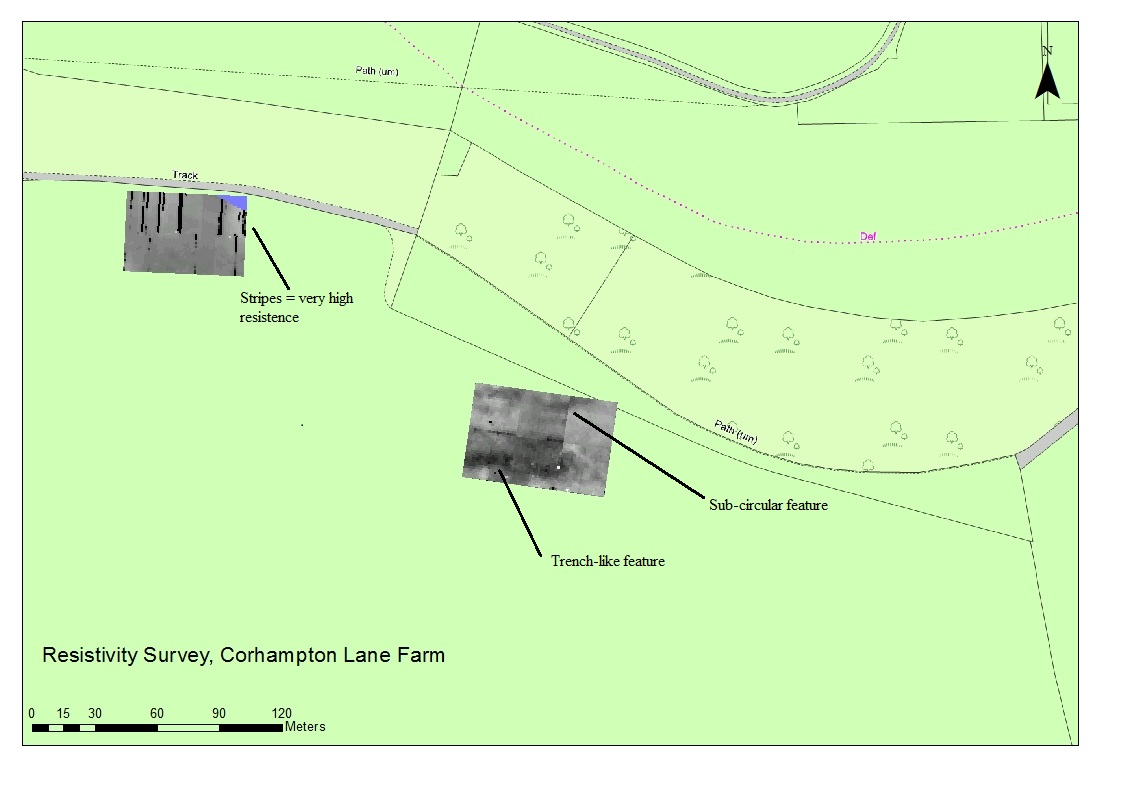

Pilot survey at Corhampton Lane Farm 20th/21st September 2013

The Project’s first Pilot Survey took place at a location on Corhampton Lane Farm. It was a community project that had the joint

aims of introducing and training local volunteers in non-intrusive archaeological techniques, i.e. non-excavation, while recovering

evidence that would hopefully contribute to our knowledge of the area during the Anglo-Saxon period. A relatively large collection

of metal artefacts, which had previously been recovered by our Project’s metal detectorists (Mike Gaines and John Whittaker), first

attracted us to the area. Moreover, an aerial photograph revealed the presence of a pair of ring-ditches: the probable remains of

Bronze Age funerary barrows.

The assemblage of metal artefacts includes a number of Anglo-Saxon objects that are typical of finds recovered from early Anglo-Saxon

graves. It is known that the early Anglo-Saxons made a practice of locating their cemeteries around earlier monuments – for an

excellent local example see the archaeological work undertaken at Storey’s Meadow, West Meon [see report in Historical section].

The assumption was therefore that one of the ring ditches was the site of the Anglo-Saxon cemetery that had produced the artefacts;

to investigate this notion a geophysical (resistivity) survey and metal-detector survey was planned. Mike and John were the experts

charged with leading the metal detecting, while the geophysics was led by Maisie Marshall, an archaeology student from the University

of Winchester.

We commenced our work on the Friday, a very warm early Autumn day and were blessed with splendid views across the Meon Valley to

Old Winchester Hill – an important prehistoric site. This day’s work centred on the eastern ring ditch, which overlooks the valley

and was considered to be the most likely candidate for the location of the Anglo-Saxon cemetery. This idea was based on the fact

that the burial ground would have been visible to people living in the valley below and conforms to the pattern observed elsewhere,

most notably just along the Meon at Shavards Farm.

After a brief introduction to the area and its Anglo-Saxon background the volunteers divided into two groups. One group set about

gridding out an area over the probable location of the ring ditch in preparation for the resistivity survey. The importance of

having accurate grids, which acted as the recording framework for the surveys, was explained to the volunteers. The second group

were using metal detectors and instructions were given on interpreting the different signals that metal objects produce and how to

locate objects effectively by adopting a systematic and rigorous approach.

Resistivity survey. In total an area of 60x40m was divided into six 20m squares and surveyed (Area 2, see Fig. 1) using

1m intervals and transects. A RM15 resistivity meter was used. The meter transmits an electric current through the ground and the

resistance is measured and recorded. Each volunteer gained experience in using the resistivity meter, in addition to moving the

guidelines that marked out the transects. Very good progress was made and the whole area was surveyed within the day. A preliminary

assessment of the data revealed the faint outline of a ring ditch but no other features, certainly nothing that could be interpreted

as being indicative of an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery.

Metal detecting. The volunteers soon appreciated that metal detecting is harder than it first appears. In particular, the

weight of the machine combined with the demands of keeping the search coil level led to a few aching arms! As already mentioned, the

area had previously been searched so the number of significant finds was quite low. The highlights include several coins (Roman,

medieval and more modern), plus a handful of objects that could possibly have come from early Anglo-Saxon graves, such as a copper

alloy ring and some copper alloy fragments.

In contrast to Friday, Saturday was much more autumnal, but we welcomed some new volunteers and the focus shifted to the western

ditch where another 60x40m area was targeted (Area 1, see Fig. 1). Once again, progress was good, although at one point technical

difficulties with the resistivity meter, i.e. the logging of very high values as indicated by black stripes on Fig. 1, almost

resulted in the survey being abandoned! But at the last minute it decided to play ball and the team pushed on to complete the area.

Metal detecting also moved over to this area and a similar range of finds to the previous day was recovered.

The geophysics results from the Saturday did not reveal any obvious archaeological features; in fact the area looks to be

sterile. This is frustrating because we were confident that the grid was sited correctly over the ring ditch. The difficulties that

the equipment suffered could have affected the recording of the data. Furthermore, when Maisie reprocessed the results from Friday

in a different way, as advised by staff from the University, the ring ditch disappeared! There is, however, another part of a

sub-circular feature, which although it is in the wrong place for the original ditch, is interesting. In addition, a strand of

higher resistance can be seen extending through two of the southern grids, approximately 5m wide and quite straight. It could be a

trench of unknown purpose or a feature of the natural geology.

Overall, the two days surveying at Corhampton were very enjoyable for all who took part and although the results are not

particularly archaeologically significant, the training provided to complete novices was successful. We would like to thank all the

volunteers who participated in the survey, particularly for showing such interest and enthusiasm. The area still has potential as

revealed by the features discovered in Area 2 and we have plans to reinvestigate it, probably using a different geophysical technique.

The Pilot Surveys are an opportunity for the experts to refine their approaches, not only in how we implement and carry out surveys

but also how we deliver training to volunteers. The experience of this first survey, although generally positive has identified

several things that could have been done more effectively and in the forthcoming surveys we will be making some changes to the way

certain practices are implemented.

Nick Stoodley & Maisie Marshall

Click onto map to enlarge

×

Figure 1. Survey results

A resource of links to prior Surveys carried out in the Meon Valley

Below is a collection of links to reports from geopysical surveys carried out in the Meon Valley area on behalf of the Saxons

in the Meon Valley Project. These were funded by the National Lottery and The Friends of Corhampton Saxon Church.

|